Updated July, 2025. Sections of this text were reworded for clarity using LLMs.

– Find part 1 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart1

– Find part 2 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart2

– Find part 3 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart3

Find our free & paid Eureka & BTC resources here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/TpTFollow

Hi everybody.

Here is the fourth and final post on this topic. We’ve loved reading your comments about integrating BTC into your classroom. Please keep telling us about your journey with BTC. Have you heard it being discussed in your school? How has your admin reacted to it?

Some points to note:

- After each approach is outlined, we will highlight why that practice is important and beneficial to teachers who use the Eureka curriculum.

- When you see (Liljedahl, 2019), know that I’m referencing information directly from the Building Thinking Classrooms text.

- Those who have implemented the approach, please comment with your thoughts, ideas, and resources.

- The post will take approximately 10 minutes to read. Grab a coffee and enjoy!

– We recommend watching this video to get a snapshot of a Thinking Classroom in real life:

On that note, let’s jump into our final exploration of “Building Thinking Classrooms” by Peter Liljedahl within the Eureka program.

Practice #11: How Students Take Notes In A Thinking Classroom

Reading this chapter reminded me of my own days preparing for the Leaving Certificate, Ireland’s version of the SATs. Every afternoon, I would spend three hours copying “notes” from textbooks. By the end of the year, I had filled 15 A4 notebooks with paraphrased sentences. Did those notes help me? Not at all. What I really needed was someone to teach me how to take useful notes. Even better, I wish someone had handed me a note-taking template like the one I’m about to share.

Taking notes effectively is a skill. Liljedahl points out the problems with the traditional method of having students write while the teacher talks. Students either cannot keep up, never look at the notes again, or avoid note-taking altogether. So how do we help students consolidate their learning?

In my classroom, students typically complete their learning during the problem set or concept check, and that’s often enough. However, that’s not to say that my students never take notes or consolidate their misconceptions. I’m a firm believer in the idea of deliberate practice. I know that 80% of my students will understand the concept from that day’s lesson. Therefore, why would I have them spend up to 15 minutes writing notes on the day’s learning? Instead, I use note-taking, a response technique for when misconceptions are shown in the End of Module assessment.

After reviewing the assessment together, I ask students to identify the questions they missed. They then spend around 30 minutes writing notes on those concepts.

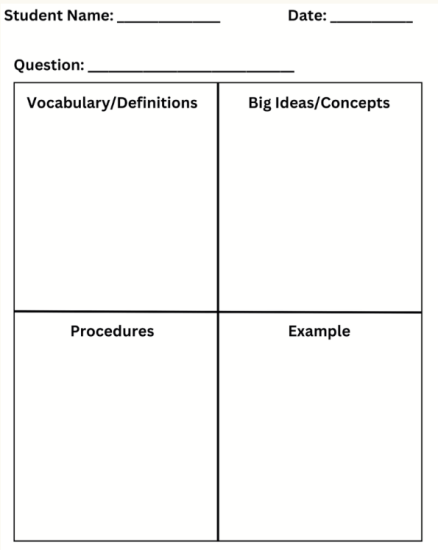

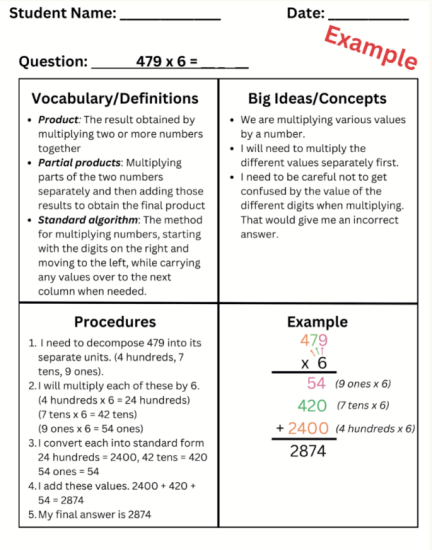

To make this more effective, students need guidance. A blank notebook page will not cut it. They need structure to break down the concept clearly. Liljedahl offers a great framework for this, and it closely mirrors the note-taking template we’ve created. Our template gives students specific sections to work through so they can fully process the idea. You can see an example in the image below, along with a breakdown of partial products. Download our amazing note-taking template for free using this link.

This focused, purposeful note-taking has been a hit with students. They take pride in the notes they create and see them as a meaningful way to fix their misconceptions. They also understand this process as part of being in a Thinking Classroom. It keeps them engaged and helps them take ownership of their growth.

🔴 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

Eureka is a spiraled program. Mastery is not expected on the first attempt, and students will revisit concepts throughout the module. Rather than forcing students to take notes after every lesson, give them the space to review and reflect over time. Wait until the End-of-Module assessment reveals which concepts still need work, and then use structured note-taking to help students build lasting understanding. When paired with the review approach in Practice #13, this empowers students to take further responsibility for their learning.

Practice #12: What We Choose To Evaluate In A Thinking Classroom

Peter Liljedahl reminds us to “assess what we value” (Liljedahl, 2021) in our thinking classrooms. But first, we need to ask ourselves: what exactly do we value? Take a moment and think of the three skills or competencies you most want your students to develop. Got them? Great. Scroll on.

In his research, Liljedahl found that teachers almost always landed on the same three core competencies:

1. Perseverance

2. Willingness To Take Risks

3. Ability to Collaborate

Do those resonate with you? Whatever your top three may be, the key is to name them clearly and build your evaluation practices around them.

Traditionally, rubrics have been used to assess learning, but most rubrics are written from the teacher’s perspective and packed with confusing language. Students often struggle to self-assess using them. Deciding between a 2 or 3 out of 4 can feel more like a guessing game than a learning tool.

Liljedahl suggests a better option: use a co-constructed, non-numeric rubric focused on a specific competency.

Okay, let’s break down what that means.

Targeted competency: Pick one skill you want students to build, such as collaboration, perseverance, risk-taking, or problem-solving.

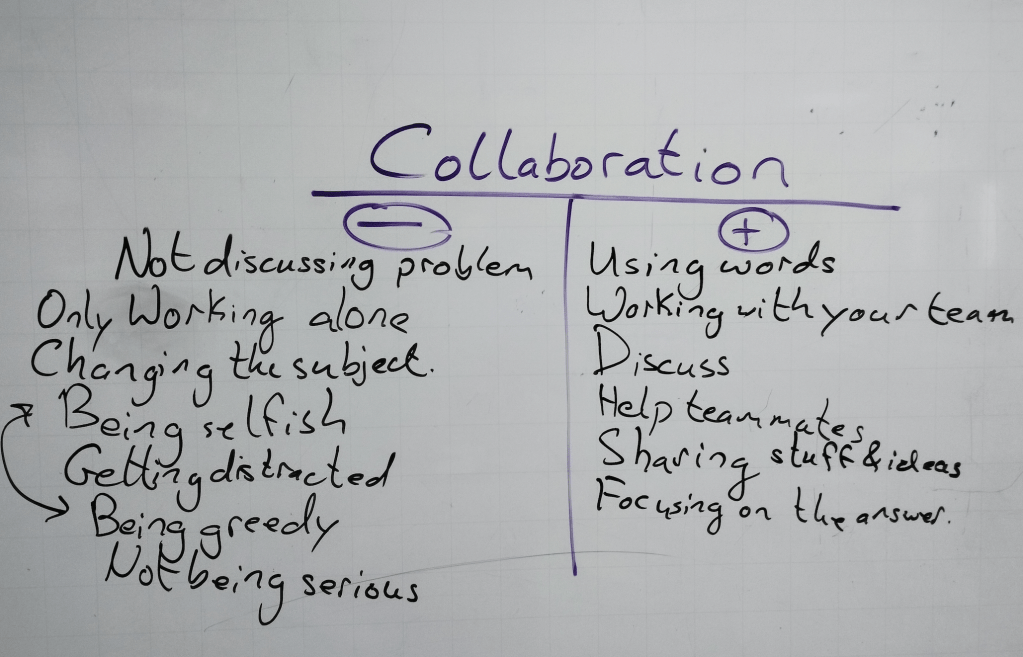

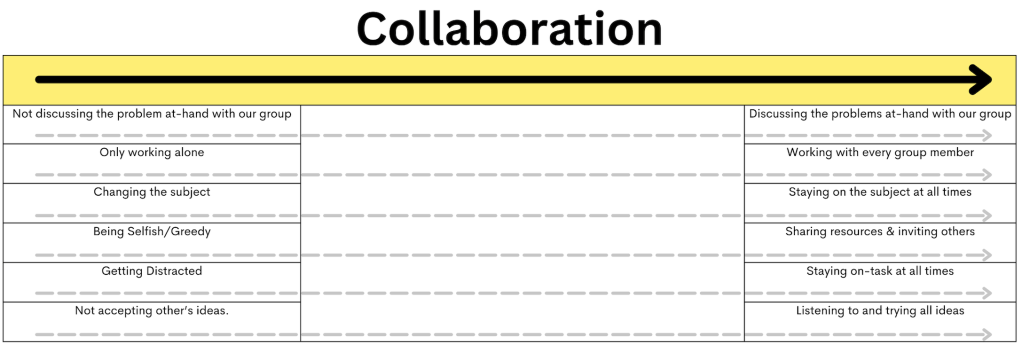

Co-Constructed: Spend 3–4 minutes discussing the competency as a class. Together, decide what behaviors show strong use of that skill and what behaviors show a lack of it.

Use a Continuum, Not Numbers: Instead of giving students a score, the rubric works like a sliding scale. On the left are the actions that don’t support the competency. On the right are the ones that do. This format is simpler, more transparent, and easier for students to engage with.

I co-created a rubric for collaboration with my students last week. Check out how we co-constructed the parameters together below.

Using the parameters we developed together, I created the rubric below in Canva. Notice how the desired behaviors are listed on the right. Students can point to where they fall on the continuum, based on how closely their actions match those expectations.

For example, my class co-created a rubric for collaboration last week. Since we’re working on a unit about energy transfers that requires a lot of teamwork, I keep the rubric handy. If a group drifts off-task, I quietly place it on their table. That gentle nudge is often all it takes to get them back on track.

You can get the above template for co-constructing rubrics, along with a guide & sample rubrics here.

🔴 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

This approach won’t help when marking end-of-module assessments, but it’s incredibly valuable during daily instruction. The Eureka program does not prioritize group work, which limits opportunities for students to build collaboration and problem-solving skills. Adding BTC-style tasks gives students the chance to work together meaningfully. Co-constructed rubrics then help you guide and support that collaboration with clarity and intention.

Practice #13: How We Use Formative Assessment In A Thinking Classroom

If someone took away your phone, your map, and every road sign, could you still find your way to the nearest grocery store? What about the next town? The next city? Chances are, you’d struggle without some kind of guide.

The same goes for students learning math. Eureka expects learners to make connections between concepts across a module, but it rarely gives them a clear roadmap to do so. Peter Liljedahl emphasizes the importance of giving students those guides. His research shows a striking difference in performance between students who can break a unit into subtopics and those who see it as one giant block of content. Students who recognized the unit’s structure scored around 90%. Those who didn’t typically scored below 75%.

So, we need to give our learners these guides! The good news for Eureka teachers is that the program is perfectly structured for this! Read on to find out how.

🔴 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

Each module is divided into topics that explore different parts of a broader concept. That makes it easy to create visual “maps” of the unit. At the start of each module, I walk students through this map, quickly highlighting what each topic will cover. Throughout the unit, we revisit the map to show how current content links back to previous ideas or leads forward into what’s next.

You can see this in action on pages 235-240 in the BTC text. However, where Liljedahl has input numbers, I input questions that grow in difficulty as the rubric moves from Basic to Intermediate.

Creating this map helps in the following ways:

1) It helps students see the structure of their learning. They can better understand how each lesson fits into the big picture.

2) It’s an excellent revision tool. Instead of using Embarc’s review sheets, which often mimic the assessment, I give each student a copy of the module map. They spend 40 minutes answering the most advanced questions they can. If they can do so without help, they know they’re ready. If not, they write notes for that question and revisit it.

Couple that with our “Fair and Squared Math Mystery Assessment Reviews” for classwork or homework the week before, and you’ll have a group of learners who are confident, prepared, and truly understand the content, not just the test format.

Practice #14: How We Grade In A Thinking Classroom

Okay, I have a riddle for you:

Always on the prowl, with a critical eye,

For numbers and stats, they often pry.

They’re not a student, teacher, or in the band,

But in the school’s corridors, their demands often stand.

Who is this person, with data they’re smitten,

Always asking for more, as if you’ve been bitten?

If you answered, “The school’s data-focused administrator,” you are absolutely correct! 😂

Data plays an important role in education. It helps us tailor instruction and support student needs. At the same time, it is often collected to satisfy leadership teams who need numbers for reports and evaluations.

So how do we balance the student-centered ideas from Building Thinking Classrooms with the number-focused systems many schools still use?

Peter Liljedahl recommends moving away from “event-based grading,” where a single test determines performance, and instead using “evidence-based assessment,” where we gather insights over time. It is a strong approach, but most schools still require module assessments and expect those scores to be submitted.

Here’s how I please admin while upholding the concepts of BTC. Thank you to my colleague, Sam for recommending this one!

I now track two kinds of data:

1) Module assessment scores, which meet school requirements.

2) Thinking classroom competencies, which reflect the learning behaviors we value.

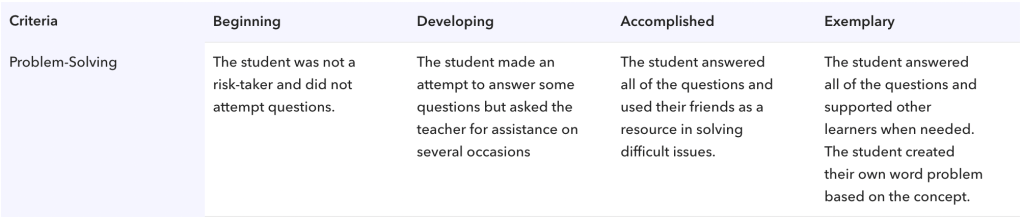

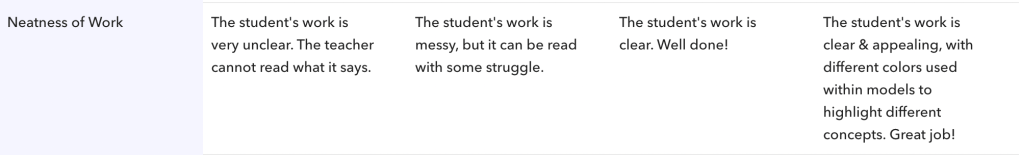

After students complete their Problem Sets or Concept-Checking Questions, they upload their work to Toddle (a platform similar to Seesaw). I attach a simple rubric that highlights the behaviors we want to encourage, such as:

- Did the student show all their work?

- Was their thinking clearly explained?

- Did they understand the concept?

- Was their work neat?

- Did they collaborate with their group?

These rubrics can be adjusted to match any skill you want students to build.

Over time, students begin to recognize that learning behaviors matter. They start to focus more on clarity, teamwork, and persistence—not just getting the right answer.

When it is time for report cards or parent meetings, I can speak to both their academic progress and their growth as learners. It gives a fuller picture of their development.

Check out our two examples below.

🔴 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

In the traditional Eureka approach, Problem Sets are used to practice the day’s skill and often focus only on accuracy. By using rubrics that highlight important learning behaviors, we help students see that how they learn is just as important as what they learn. It reinforces the idea that they are part of a classroom where thinking, collaboration, and perseverance are valued every day.

❤️ That wraps up our final post in the Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics series by Peter Liljedahl. Thank you so much for following along. We hope these posts sparked fresh ideas and gave you practical ways to bring more thinking, collaboration, and joy into your math classroom.

Homework for the Teacher (That’s You!)

1. Choose one BTC practice you haven’t tried yet and give it a go this week.

2. Co-create a simple competency rubric with your students.

3. Swap a traditional mini-lesson for a consolidation session using student work.

4. Create a “learning map” for your next unit to guide student revision and reflection.

📝 We’d love to hear from you!

Send your feedback, suggestions, or takeaways to info@fair-and-squared.com or drop a comment below. What stuck with you? What are you excited to try?

Thanks again for reading. Want to learn more about how to boost Eurak scores? Check out our 5 Secret Weapons For Eureka Success post.

To find all of our resources, including items that will support you in setting up a BTC framework in your classroom, check out our TpT page here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/TpTstore

Happy learning!

The Fair and Squared Team 🕵️♀️🕵️♂️👩🎓👨🎓🌟