Updated July, 2025. Sections of this text were reworded for clarity using LLMs.

Okay folks, following on from last week, here’s our second update of the BTC in Eureka post.

– Find part 1 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart1

– Find part 3 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart3

– Find part 4 here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/BTCBlogPart4

– Find our free & paid EngageNY & BTC resources on our page: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/store

Some points to note:

- After each approach is outlined, we will highlight why that practice is important and beneficial to teachers who use the Eureka curriculum.

- When you see (Liljedahl, 2019), know that I’m referencing information directly from the Building Thinking Classrooms text.

- Those who have implemented the approach, please comment with your thoughts, ideas, and resources.

- The post will take approximately 10 minutes to read. Grab a coffee and enjoy!

– We recommend watching this video to get a snapshot of a Thinking Classroom in real life:

On that note, let’s dive into the fourth practice to develop a thinking classroom within the Eureka framework.

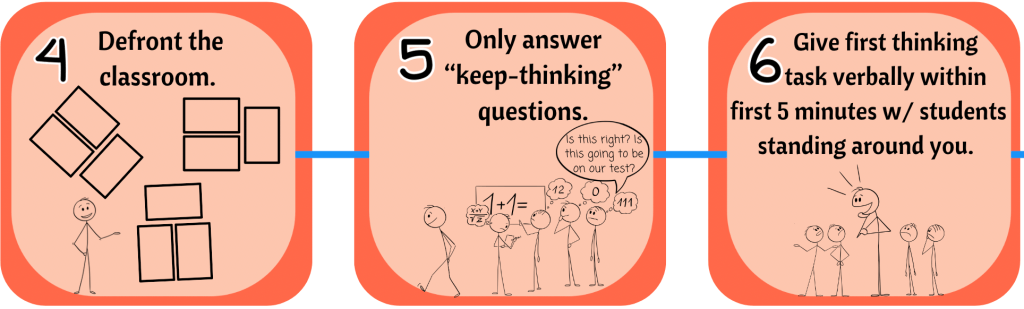

Practice #4: Defront the Classroom – The Board Isn’t the Boss Anymore

To encourage deep thinking, we need to move away from the traditional front-of-classroom setup. This means that we should try to not have a “front” from where we teach in our classroom.

“Every time we worked in classrooms that were super organized we had more difficulty generating thinking. Classrooms need to have just-right amount of disorder for thinking to flourish.” (Liljedahl, 2021).

Arrange furniture so that students face each other in groups, rather than facing the front. Ideally, group tables should be positioned away from the vertical whiteboards to allow space for movement and clear sightlines.

![]() 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬? As we discussed in blog post #1, the ultimate goal of the BTC approach is getting students to think through problems. The Eureka program doesn’t always promote this concept. Altering the layout of classroom furniture & de-fronting the classroom signals to students that thinking and collaboration are valued more than quiet compliance.

𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬? As we discussed in blog post #1, the ultimate goal of the BTC approach is getting students to think through problems. The Eureka program doesn’t always promote this concept. Altering the layout of classroom furniture & de-fronting the classroom signals to students that thinking and collaboration are valued more than quiet compliance.

The flexibility of movement in the classroom will promote the idea that yours is a thinking classroom and those that work within it are active constructors of knowledge, not passive receivers of it. This is the practice I struggle with most, and that’s okay! Thinking still happens in my classroom, so I remind myself that progress matters more than perfection. You should, too. (Insert Kumbaya song here) 😛

Practice #5: How We Answer Questions – With Questions, of Course

Pop quiz: how many questions will a typical teacher answer every day? Answer: 200-600!! Share that one with your learners 😉

While it may seem that answering student questions always helps our students learn, Liljedahl found that this is not always the case.

Liljedahl identified 3 different types of questions that teachers get asked. They are…

𝟏) 𝐏𝐫𝐨𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬: These are questions that students will only ask their teacher when the teacher is close by. They do this to conform to the role of a student, even if they know or can find the answer themselves. (Example: “What class do we have after recess?” “How many questions do we need to answer?”

𝟐) 𝐒𝐭𝐨𝐩-𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬: Thinking takes effort, and students often prefer to avoid it if they can. Therefore, they will often ask their teacher stop-thinking questions. (Example: “Do we have to learn this?” “Is this answer correct?”

Liljedahl found that out of the hundreds of questions teachers receive each week, around 90% fall into the proximity or stop-thinking categories. It’s important that we encourage as much thinking as possible from our students and therefore, it’s important that we avoid answering these questions. So, what about the other 10% of questions that we get asked? They are known as…

𝟑) 𝐊𝐞𝐞𝐩-𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐤𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐐𝐮𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬: These are asked by students so that they can further engage with the task at-hand. They are usually about clarification or extensions. (Example: “Can we get the next set of questions?” “Can we solve this problem using a tape diagram as well as the standard algorithm?” These questions drive further thinking and should be encouraged in our classrooms.

I informed my students about these 3 types of questions. They know that they have to think to learn and they very quickly stopped asking proximity & stop-thinking questions. Students will even correct their classmates when they hear proximity questions being asked. Liljedahl recommends acknowledging to students that you heard their question and redirecting it with another question or statement. “What do you think?” “What makes you ask that?” “I think it would be better if you explained your answer to me rather than me telling you the correct one.” Yes, even walking away is an option when students ask a non-thinking question. It may feel abrupt at first, but it reinforces the shift toward a student-led thinking environment.

![]() 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

When Eureka lessons focus on modeling Problem Sets, students learn that the teacher holds all the answers. This teaches them to rely on the teacher anytime they’re unsure, rather than working through the problem independently. Encouraging only keep-thinking questions shifts the responsibility to students, prompting them to seek answers through their own reasoning, classroom resources, or peer support. This shift places students at the center of learning and further defines the teacher’s role as a facilitator, not a deliverer of information.

Practice #6: When, Where, and How to Give Thinking Tasks – The Fast & Curiou

When To Give Thinking Tasks– To get the most out of a thinking task, it should be assigned within the first five minutes of the lesson. If a new concept needs to be introduced, aim to keep that explanation short and focused. Research shows that student attention drops off quickly after the five-minute mark.

As Liljedahl puts it, “The further into the lesson the teacher waited before giving the task, the less effective it became.” (Liljedahl, 2021)

Sticking to this five-minute window helps maintain focus and builds positive energy in the classroom. It signals to students that thinking is expected right from the start.

Where To Give Thinking Tasks– Liljedahl recommends giving the task while students are standing. Personally, I deliver thinking tasks to my fourth graders while they’re seated on the carpet. Standing might be more effective for middle or high school students, but in my experience, sitting doesn’t seem to interfere with engagement, so long as the task is given within the first five minutes.

When assigning a curricular task, I usually use the final Problem Set question from the Eureka lesson. If you prefer, feel free to use any question that will help students understand the lesson’s learning goal.

How To Give Thinking Tasks– Liljedahl suggests giving the task orally first, while writing only the key information on the board. This “textual residue” helps reduce cognitive load and encourages students to build their skill in interpreting word problems. It’s important not to write the full question, just the essential points.

Here’s an example from Grade 4, Module 2, Lesson 2:

Original word problem:

“Javier’s dog weighs 3,902 grams more than Bradley’s dog. Bradley’s dog weighs 24 kilograms 175 grams. How much does Javier’s dog weigh?”

Textual residue on the board:

“Javier dog: 3902g > Bradley’s dog.

Bradley’s dog: 24kg 175g.

Javier’s dog?”

![]() 𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

𝐖𝐡𝐲 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐄𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐤𝐚 𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬?

Eureka mini-lessons can sometimes lead to passive learning, with students simply watching the teacher solve problems. But students are far more engaged when they’re given the chance to jump in and tackle challenges themselves. By presenting the task within the first five minutes of the lesson, you maintain focus and create a sense of flow that keeps students invested.

Because Eureka’s Problem Set questions are often word-heavy, it’s essential for students to develop the skill of figuring out what they’re being asked. Giving tasks orally while writing only the key information, or “textual residue,” helps them build this skill over time. You’ll likely find that students become more confident at interpreting problems on their own.

Liljedahl explains, “giving tasks verbally produced more thinking-sooner & deeper- and generated fewer questions at every grade level.” (Liljedahl, 2021)

![]() That wraps up our look at Practices 4, 5, and 6 from Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics by Peter Liljedahl. While the first three practices focus on how to introduce BTC routines to your students, these next steps are all about shifting your teaching behavior. Each one nudges you further into the role of facilitator and helps center your classroom around student thinking.

That wraps up our look at Practices 4, 5, and 6 from Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics by Peter Liljedahl. While the first three practices focus on how to introduce BTC routines to your students, these next steps are all about shifting your teaching behavior. Each one nudges you further into the role of facilitator and helps center your classroom around student thinking.

Try the Following This Week – Homework for the Teacher 😛

- Rearrange your classroom furniture to eliminate the “front” of the room and encourage student-facing groupings.

- Give your thinking task within the first five minutes of the lesson, keeping any concept intro under five minutes.

- Present a word problem orally and only write the key “textual residue” on the board — leave the full question off.

- Send us an email and tell us how it went! info@fair-and-squared.com

Please post any responses/thoughts/comments/ideas/questions below!

Thank you for reading! ![]()

See you soon for Part 3 of Building Thinking Classrooms In The Eureka/EngageNY Program,

The Fair and Squared Team 🌟

PS. To check out all of our free & paid resources, find our TpT store here: https://edu.fair-and-squared.com/TpTstore

4 responses to “14 Steps for Building Thinking Classrooms For Eureka / EngageNY Math (Part 2)”

Fair and Squared: I stumbled upon your blog while researching how to better teach Eureka math in 4th grade. I have also studied Liljedahl’s BTC book, and I’m devouring your posts on implementing BTC with Eureka math. THANK you for sharing your ideas! Another thing we have in common is Zearn. I love how it matches Eureka and is much more engaging than the practice pages. Now, to ask for your expertise and experience! Will you please share your daily schedule?? Also, would you please give me some advice on how to best use Zearn if it’s not an option for students to complete at home? (Rural area where several families do not have internet)….

I still can’t believe I found someone who has experience with all 3 resources that would make up my dream math block! I’m just struggling with getting it all together! Help please? Thanks so much in advance!

LikeLike

Hi Erin,

I was so glad to read your enthusiastic post! I’m glad that the blog has given you ideas. Merging BTC and Eureka is a winning formula! It worked wonders for my kids last year.

Regarding your Zearn issues, it’s a real problem. I was stumped! ChatGPT has become a real friend of mine over the past year. Here’s what it said in response to your query. I think points 1 and 3 are particularly interesting!

1. Integrate Zearn During Math Block: Since Zearn mirrors Eureka lessons so well, try using it in your daily math block. A few options include:

– Rotations or Centers: Set up Zearn as one of your math centers. While one group works with you on a specific Eureka lesson, another group can complete the corresponding Zearn lesson. This way, students get individualized practice without needing homework time.

– Independent Practice Time: Use Zearn as an option during independent practice. Students who are ready for digital reinforcement can work through Zearn while others continue with hands-on tasks or paper-based Eureka practice.

2. Offline Resources and Guided Support: If internet access is limited even during school hours, download and print Zearn’s Mission Journal pages or activity sheets ahead of time. These align with Zearn’s digital lessons and provide students with similar practice.

3. Whole-Class Zearn Activities: For particularly tricky concepts, consider running a Zearn lesson as a whole-class activity. Go through the digital lesson on a shared screen, letting students interact with questions. This method helps all students engage with the content, even if they don’t have internet access at home.

Could you use Zearn in stations? If not, would it be beneficial to use Zearn as the concept development, with you leading the learning?

What do you think?

Looking forward to hearing from you! 😁

Ronan from Fair and Squared

LikeLike

Thank you for your quick response! And for your ideas to help with implementing Zearn. I’m You said on your blog that you use a problem from the practice problems to start your lessons in BTC style. Would mind expanding on that a little please? I found the application problems for Eureka, are those the ones you use? Are you also doing the thin slicing? Does that work well with Eureka problems? About how long do your kids last at the boards?

Actually, would you also please explain what your math block looks like from start to finish?

I can’t even tell you how excited I am to find a fellow educator using BTC in fourth grade. The kids are younger, but I think they can still do it!

Thanks for your collaboration with me! Erin

LikeLike

Hi Erin,

My apologies for the delayed reply. Life held me for a little while!

Regarding Zearn, have students complete the next day’s lesson the night before. This flipped classroom method will ensure students come to class with a solid foundation of what’s to come. The problem sets/ boardwork consolidates their learning.

Regarding the Problem Sets, I choose one question from the set that I feel will allow the students to answer all of the other questions. It’s usually one of the last questions on the Problem Set. I’m not talking about the Application Problem. Those are usually based on previously learnt content.

I don’t do thin slicing. I use extensions to push learning forward or to review previously learned content. For example: Today’s question says: “Barry drove 4375m to work and home again. How far did he drive.” When students get the right answer, I might have them round the 4375 to the nearest 100 on a vertical number line and then find the answer. They decide if the answer is reasonable (review of rounding). Or I might have them convert that to km and m (attempting the next day’s lesson of measurement conversions)

Kids are at the boards for about 15 minutes and I consolidate on one of their work for about 3-5 minutes. If all students nailed it, I don’t consolidate and monitor their problem set work carefully.

My math block looks as follows: I give the task and write “the fragments” of the question on the board (as instructed in the BTC book): 1 minute

I choose random groups with lollipop sticks: 2 minutes.

Students work on the question, I give hints/extensions and direct members to see other groups’ work: 10-15 minutes

I consolidate using one of the group’s work (I show an incorrect group’s work first and maybe then show a correct group’s work).

Remember, you have to see the forest for the trees. The main goal is to get students thinking and to get through the lessons. Trust the process!

Let me know how it’s going and whatever questions you have next. I’ll reply more promptly next time! 😁

LikeLike